Galveston Bay Water Monitoring Duo Up for the Test

- August 25, 2022

- News

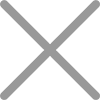

Dave Bulliner is a self-proclaimed “lab rat.”

“I’m just like the little rats that run around in the lab,” he said with a smile.

Bulliner’s passion for lab work goes back to his college days at Southern Illinois University. He was a student worker in the zoology department, tasked with maintaining the channel catfish tank. His duties included routinely checking the oxygen levels and feeding the fish.

Following a 44-year hiatus from the lab to pursue a career in retail management, the Illinois-native finally donned a white coat again in 2011. He wanted to do something “a little bit more productive” in retirement and joined the Galveston Bay Area Chapter of the Texas Master Naturalists. There he learned about an opportunity to do bacteria testing as part of the Galveston Bay Foundation’s volunteer water quality monitoring program.

Following a 44-year hiatus from the lab to pursue a career in retail management, the Illinois-native finally donned a white coat again in 2011. He wanted to do something “a little bit more productive” in retirement and joined the Galveston Bay Area Chapter of the Texas Master Naturalists. There he learned about an opportunity to do bacteria testing as part of the Galveston Bay Foundation’s volunteer water quality monitoring program.

“I said, ‘Pow, that’s what I want to do,’” Bulliner recalled.

The foundation first started monitoring the water quality of Galveston Bay in 1992. Originally called The Estuarine Sampling Team (TEST), the program relies on a team of volunteers to collect and test water samples from locations around the Bay each month.

The data loving Bulliner was hooked.

“I think data is one of the most important tools that scientists have to use when they go back and check things they’ve done and what they want to accomplish,” he said.

Bulliner shared his passion for bacteria testing with Mike Petitt, a retired physician who joined the Texas Master Naturalists in 2018. Bulliner was Petitt’s mentor and told him about the volunteer water monitoring team. It did not take much convincing for Petitt – a native Houstonian who grew up going to the Bay – to see the importance of the program.

“We live down here. It’s an important thing to make sure our Bay is maintained,” he said. “If you don’t measure it, you don’t know it.”

At the beginning of each month, Bulliner and Petitt can be found working together in the water quality lab at Galveston Bay Foundation’s headquarters in Kemah, testing samples from the Bay’s brackish waters for bacteria, specifically enterococcus.

The leading cause of enterococcus in the Bay is fecal matter, most commonly from dogs. Septic tank overflow and over fertilization of yards can also cause spikes in enterococcus.

Elevated enterococcus levels are especially common after dry periods followed by heavy rainfall, when a “first flush” effect occurs.

“Think about that stuff when a heavy rain falls. Where does it go?” Bulliner asked rhetorically. “It causes problems.”

To detect any potentially harmful levels of enterococcus, the two men always use the same procedure. They meticulously follow a laminated checklist – despite having done the same process countless times – to make absolutely sure they do not miss a step and have consistent results.

“Just like pilots use a checklist,” Petitt said.

Arguably the most time-consuming part of their duties is the paperwork. Multiple signatures are needed when a sample is received. The sample number, location where it was taken, date and time are all recorded into a log. Labels then need to be created and matched with the appropriate sample. Even the temperature of the incubator, which is always set at 41.0 degrees Celsius (105.8 degrees Fahrenheit), is checked and recorded.

The actual testing process begins only after everything has been carefully logged and labeled. 10 milliliters from a sample is sucked up through a pipette and dispensed into 90 milliliters of ionized, enterococcus-free water. The mixture is then introverted 10 times.

A packet of Enterolert, an agent that is ingested by the bacteria and has the property to glow under a blacklight, is then added to the mix and introverted another 25 times, staining the sample a yellowish color.

A packet of Enterolert, an agent that is ingested by the bacteria and has the property to glow under a blacklight, is then added to the mix and introverted another 25 times, staining the sample a yellowish color.

After letting the solution sit for a full minute, it is then carefully emptied into a sample container with 50 square wells plus one additional at the top. Bulliner and Petitt painstakingly rid the wells of any air bubbles to ensure each contains an equal amount of solution.

The sample container is then fed through a sealer before being placed in the incubator where it remains for 24 hours.

The next day, the sample containers are removed from the incubator and placed under a blacklight. If more than 33 wells illuminate, a fresh sample from the site needs to be obtained so it can be tested again. If the bacteria level in the new sample is also elevated, authorities are alerted.

Bulliner and Petitt both noted the water quality in various parts of the Bay can quickly change, but overall, they have witnessed an improvement first-hand in recent years. The Bay’s water quality grade on the Galveston Bay Report Card, published annually by the Houston Advanced Research Center (HARC) and the Galveston Bay Foundation, has gone from a B in 2015 to an A in 2021.

Bulliner admitted the experience has changed him.

“You get caught up in your work-a-day world, and you just don’t think what you’re doing to the wildlife,” he said. “It opened my eyes.”

He has since stopped fertilizing his yard, installed two rain barrels to conserve water, and planted native plants around his home.

It is his way of helping to preserve what he calls the “three W’s,” wind, water, and wildlife.

“We can only do so much while we’re on this Earth, so we want to preserve the certain areas that we do have,” Bulliner said.

Galveston Bay Foundation is currently in need of additional volunteer water monitors to take samples from sites around the Bay. If you are interested in volunteering, email us at waterquality@galvbay.org.